WHAT IF the thoughtless usage of one single word could lead to you losing your job?

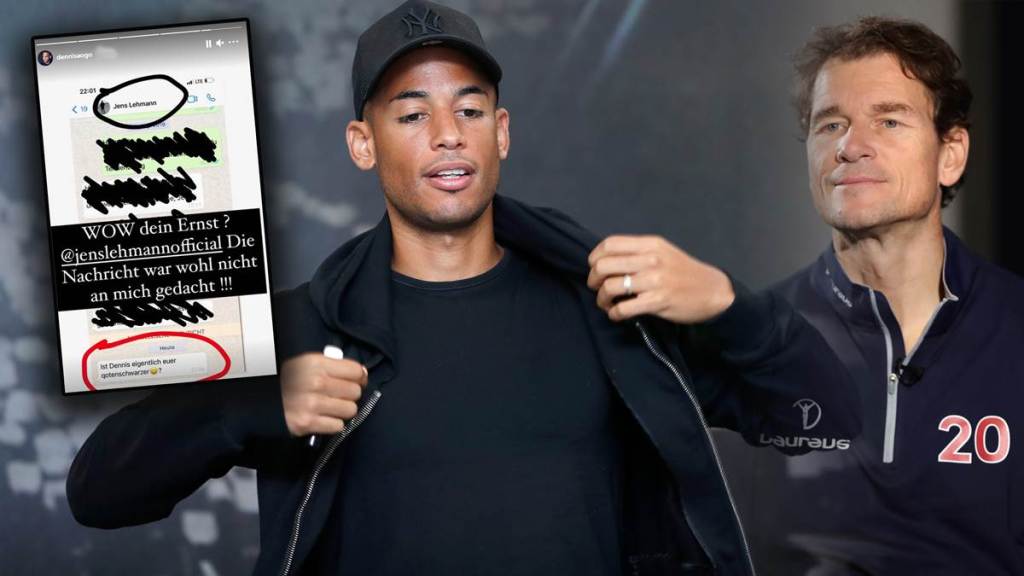

Two former German international football players had to experience this in May 2021. One was Jens Lehmann, former goalkeeper for the German national team, who sent a private WhatsApp message to former teammate Dennis Aogo, who was serving as a pundit on the TV channel Sky Sports (see e.g. Bristow 2021). In the message, which was probably not intended for Aogo, Lehmann called him a ‘Quotenschwarzer’ which can be roughly translated as ‘token black guy’. Aogo then posted the message on his social media site, everything became public, and within a matter of hours, Lehmann lost his job as advisor of Bundesliga team Hertha BSC and the majority of his sponsorship contracts. Ironically, Aogo himself would be dismissed from his job as a pundit just a day later for his usage of the term “gassed” during a live broadcast, which (in Germany) invokes a connection to the Holocaust. Naturally, both cases sparked a debate on social media, with public opinion being divided. One side argued that both deserved their dismissal because their statements were unacceptable, while others claimed that everyone was becoming way too sensitive and that the firing was an overreaction to a non-issue, since everything was just ‘banter’.

This case serves as a great example of how so-called ‘political correctness’ shapes public discourse and how there is a spectrum of views when it comes to its validity. Toynbee (2009) for instance argues that the phrase ‘political correctness’ “was born as a coded cover for all who still want to say Paki, spastic or queer, all those who still want to pick on anyone not like them, playground bullies who never grew up.” She describes the politically correct society as “the civilised society, however much some may squirm at the more inelegant official circumlocutions designed to avoid offence. Inelegance is better than bile.”

PC language serves as a tool to reduce discrimination and to avoid offending minorities by replacing terms that could be considered offensive with other, more neutral terms – or by outright avoiding the usage of certain terms completely. Since many terms used for years have a discriminating effect on minorities and certain social or ethnic groups, PC language aims to remove these undertones from everyday language in order to avoid these instances of discrimination.

Decency or faddishness?

One would assume that it would be natural to treat this as a noble cause, since PC language advocates for decency and politeness. But there are many who are suspicious of PC language and strongly oppose its usage. O’Neill (2001) for instance, takes issue with Toynbee, arguing that PC “is narrow, faddish, and highly reflexive in character, consisting in large part of euphemisms. It sometimes promotes or amounts to outright dishonesty” (p.284). He claims that the use of euphemisms can sometimes be disadvantageous for the very people PC is designed to protect. ‘Mentally retarded’ is a much more transparent (and therefore honest?) label, than e.g. ‘having learning difficulties’ (2001: 286-87).

Critics like O’Neill also claim that PC language prohibits freedom of speech. Some, such as Chait (2015) even go as far as to accuse it of being an instrument of the radical left in order to shape (political) discussion to their benefit and to be able to denounce any opposing point of view.

Now what do we make of this? It can be argued that PC language is nowadays deeply rooted in everyday conversations, at least in the public sphere. This can partially be attributed to social media, where the policing of language can be observed especially often. Chait (2015) argues that since PC flourishes on social media “where it enjoys a frisson of cool and vast cultural reach”, it now dominates the majority of any political debate, because of its reach over and above mainstream journalism.

Another point is that there is a lot of money to be made with PC language or the non-adherence of it. Chait (2015) claims that “[e]very media company knows that stories about race and gender bias draw huge audiences, making identity politics a reliable profit center in a media industry beset by insecurity”. PC language has been dominating the discourse online and between academics for many years, but recently opponents of PC language have seen a public resurgence – best exemplified by Donald Trump, who when US President, successfully vilified PC language as a tool of oppression (see Weigel 2016). And he did so very successfully. Apparently, there are many people who disagree with PC language, feeling that it diminishes their ability to say what they want. Sadly, this very large group of people can’t be ignored.

Keep it private?

But what does that mean for the usage of PC language? One argument would be that everyone should be able to say what they want…… in private. Since freedom of speech is one of the core principles of western society, no one should be banned from saying what they want – but there should be one very significant qualification. It stops when there are other people directly involved, or you are using public modes of communication. Think of it as the equivalent of shouting your opinion on a public square. If you make potentially offensive statements on the internet, you need to be prepared for the repercussions of your ‘right to freedom of speech’. So, if you are a public speaker, like a TV pundit, and you use racist, sexist or other non-PC language, you have to consider the consequences if someone is offended by your statements – and this also applies to Jens Lehmann and Dennis Aogo.

JANOSCH WAGNER, English Language undergraduate (Erasmus), University of Chester, UK

References

Chait, J. (2015, January 27). Not a very P.C. thing to say. NYmag.

Toynbee, P. (2009, April 28). This bold equality push Is just what we needed. The Guardian.