Neither of the concepts in the title are morally correct; one suggests manipulating the minds of naïve learners of English while the other implies exploiting them for money. But when the language itself is rooted in a capitalist society, which of these is the most important motive for spreading global English? And do organisations like the British Council actively influence learners’ thinking when teaching them English?

The British Council’s answer to this is that they accept that English has hegemonic influence on the societies in which it is taught but this is due to the prestige and attraction of English and is not portrayed this way intentionally (Coleman, 2011, p.333). From a personal perspective, as a British Council language assistant my intentions weren’t to manipulate the minds of 12-year-old Spanish children to think in a certain way but to enhance their English (although not ignoring my own economic gain for doing so, in the form of a salary).

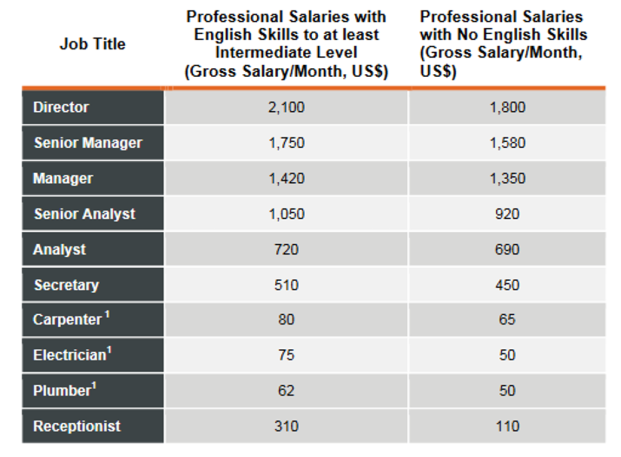

However, the reason that people learn English in the first place could be because they want to be successful in comparison to others. Gray states that a capitalist society promotes individualism as the key to freedom and success and that this ‘new economic world order’ encourages people to promote themselves in a certain way in the marketplace (2012b, p.95). The marketing of global English promotes and spreads this ideology, because learners buy into the testing and do it for the economic incentive of being paid more and being more competitive in the job market. Gray claims that putting a price on language in this way is a result of neoliberalist ideology whereby language is now sold as a skill in return for wages (2012a, pp.137-138).

On the other hand, Crystal suggests that a common language (i.e. English) is essential so that “an unfavoured linguistic heritage should not lead inevitably to disadvantage” (2003, p. xiii). However, this equality is not being fulfilled because the language skills and qualifications are not economically accessible to everybody.

IELTS (International English Language Testing Systems) and ELT (English Language Teaching) services are worth £3-4 billion year to the British economy, showing the hugely positive impact the language has for Britain (Gray, 2012b, p.97). While this is a great advantage to Britain, it is unfair for the people who contribute to this high figure. In 2012, IELTS charged £125 for English testing which was then converted to the learners’ own currencies, automatically disadvantaging people from a poorer background or from a developing country, as this is expensive (Gray, 2012a, p.156). The British Council admits that this inequality is inevitable in a capitalist economic system (Coleman, 2011 p.333). This means that people from poorer backgrounds are less likely to achieve the qualifications necessary to get a better-paid job and break the cycle of poverty.

Moreover, in Rwanda, English was made the language of education following a conflict between two ethnic groups (the Hutus and Tutsis). This led to a cut in diplomatic ties with France (due to their involvement) and therefore English replaced French’s presence in education (Gray, 2012a, pp.143-144). The British Council claim that this was a positive outcome because the economic benefits of learning English (better job prospects and higher wages in comparison to non-English speakers) would allow the economy to recuperate after the genocide. This would clearly benefit the British Council economically as well as Rwanda, as the organisation would earn money by training teachers and selling ELT resources (Gray, 2012a, p,145). However, Gray mentions Williams’ opinion that learning through the medium of English would only benefit the elitist families in which the parents already knew English to ensure that the students would be able to understand what they were being taught, again emphasising the inequality among the rich and poor (2012a, p.147).

As regards ‘cultural imperialism’, Gray claims that Rwandan President Kagame has the support of many Western governments, especially because of his willingness to restructure the Rwandan economy along neoliberal lines. This implies that Kagame is willing to adapt to a Westernised economy, thus implying that Rwanda would change their economic ideologies in favour of a British one (2012a, pp.145).

Overall, it seems that economic gain is the motive behind promoting global English, but that this is achieved through cultural imperialism because spreading the Western ideology ‘neoliberalism’ will have long term economic benefits. Promoting English as the key to success and to earning more money means that there is an ever-increasing desire to learn the language to be able to compete with others in the job market. ELT organisations rely on these learners for their vast income, but rely on the Western ideals of individualism and competition to keep attracting learners.

SUNDEEP JANDU, English Language undergraduate, University of Chester, UK

References