The debate about language as being ‘good’ or ‘bad’ permeates many areas of modern life. While highbrow linguists battle furiously over the Oxford comma, a teenage school pupil is rebuked by her teacher for stating that she ‘literally died’ because she saw a member of McFly in her local shop over the weekend.

It is traditional to describe two sides to the debate as ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ language usage. One side is the tradition of ‘prescriptivism’. Hitchings (2011) labelled a prescriptivist (those who practice prescriptivism) as an individual who “dictates how people should speak and write” (p. 23). A linguistic ‘descriptivist’, on the other hand, may claim to be non-judgemental about language use, and be more focused on describing how a language works – rather than criticising its users. While these warring factions may appear to be concrete, every person who speaks any language will have formed opinions (whether positive or negative) on the use of particular words or placing of punctuation. This means that it is impossible to be entirely on only one side of the argument.

Deborah Cameron (1995) coined the term ‘verbal hygiene’, in reference to prescriptive practices which were not just intended to complain about language use, but were “born of an urge to improve or ‘clean up’ language” (p. 1). The belief that language needs improvement is not a new phenomenon. For hundreds of years there have been attempts to ‘fix’ English by famous prescriptivists such as the 18thC writer Jonathan Swift, striving to “promote an elite standard variety, to retard linguistic change or to purge a language of ‘foreign’ elements” (Cameron, 1995, p. 9).

Prescriptivist attacks on language use occur on many linguistic levels, with much of the criticism focused on semantic word choice, positioning of punctuation and uses of slang or foreign terms. One common attack on language use in this country is centred around the influx of Americanisms (terms originating in the US) being adopted into our everyday speech. Anderson (2017) depicted his horror at the British English language being “colonised” by American English, and believed American neologisms to be “ungainly”. This discourse of prescriptive criticism can be tied (intentionally or unintentionally) to xenophobic views, something which has contributed to prescriptivists gaining the nickname ‘grammar Nazis’.

Lukač (2018, p. 5) examined the idea of “grassroots prescriptive efforts”, which she described as criticisms of language by members of the public carried out using tools such as social media sites to complain about ‘incorrect’ language usage. This strand of prescriptivism, which Lukač (2018, p. 5) regards as wildly different to that which is enabled (and encouraged) by institutions such as the education system, has brought ideas of linguistic prestige into the mainstream media. This wide exposure has facilitated a new generation of people yearning for a return of the so-called ‘golden age’ of language in this country. This fictional ‘golden age’ of language use, where it was supposed that every citizen correctly adhered to the grammatical stylings of Standard English, a dialect associated with the ‘Queen’s English’, is a myth that has encouraged the popularity of guides such as Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss. Such guides set out strict “ways to improve one’s English” (Lamb, 2010, p. 28). It could be argued by descriptivists that these guides threaten the existence of regional variations of English.

However, it is too easy to brand complaints about our language being tainted by ‘misuse’ as entirely negative and hyperbolic. Some would argue that prescriptive attitudes are important in order to preserve our safety in the modern world, as errors in communication can cause damage ranging from minor irritation to a deadly conflict between continents. Heffer (2014) highlighted the inconvenience caused by confusing malapropisms such as “enquiry” and “inquiry”, while Shariatmadari (2019) discussed how a poor choice of words led to a mistaken translation between the US president Nixon and Japanese PM Satō in the 1960s, causing already strained tensions over trade agreements to escalate.

While I believe that it is important to adhere to some language standard in a formal setting, in order to ensure effective (and safe) communication, I also think that it is essential to consider the negative effects of policing language use in our everyday lives – from the persecution of users of regional terms, to the xenophobic ideology which spreads through criticism of foreign terms. It is important to find a balance between quashing irritating behaviours, and erasing true expression. I cannot see that the debate around policing language will ever truly resolve – unless every user of language suddenly becomes accepting of other cultures and opinions.

RACHEL BRUNT, English Language undergraduate, University of Chester, UK

References

Anderson, H. (2017, September 6). How Americanisms are killing the English language. BBC Culture.

Cameron, D. (1995). Verbal hygiene. London and New York: Routledge.

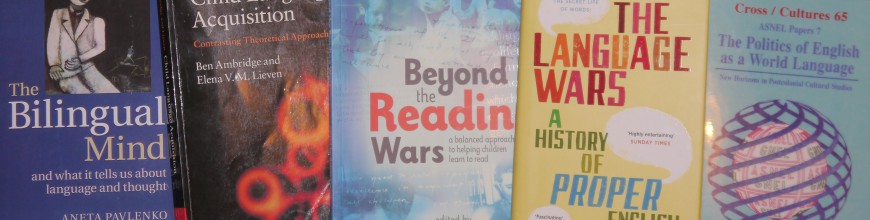

Hitchings, H. (2011). The language wars: A history of proper English. London: John Murray.

Lamb, B. C. (2010). The Queen’s English: And How to Use It. London: Michael O’Mara Books Limited.